I have a lot of friends who are asking a lot of questions about brokered conventions these days. In this series, Conventional Chaos, I’ll be explaining how a Republican party convention works… and why 2016’s convention could be very different from the dull pageants we’ve seen since the 1970s. In Part 1, we’ll go over the basics.

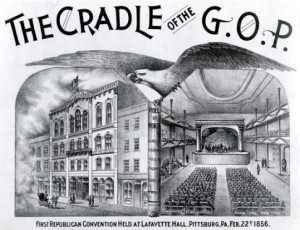

In this post, we’re going to explain how Republicans pick a president. But first, we need to explain the old process, because the modern process seems completely insane, wasteful, and incomprehensible… until you know where it came from. So, here is how Republican presidential nominees were picked from the party’s founding in 1856 until the liberal-progressive reforms of 1972:

First, you got together with your neighbors of the same political party in a gathering called a “caucus.” At the caucus, you would help elect a few of your wisest, most charismatic, most trustworthy neighbors as state delegates. Those delegates would then be sent to the state convention, where state delegates from all over the state would gather, each representing the Republicans of their own towns and districts.*

At the state convention, state delegates would discuss party business, finances, and policy, and would hold internal elections to decide who would get to run as the Republican candidate in major races (like for governor). Finally, in presidential election years, the state convention would elect its wisest and savviest (typically its top political office-holders in the state) as national delegates to attend the national convention.

At the national convention, a national party platform was set and a presidential and vice-presidential candidate were officially chosen. At the start of a national convention, you often had no idea who was going to win. Delegates often showed up undecided (this was a time when you might literally have never seen or heard any of the candidates speak before, though you would probably have read some of their speeches in the newspapers), and engaged in fierce debate, which often lasted several days, punctuated by an official vote every few hours to see where people stood. (A bit like a papal conclave.) As it became clear that this candidate or that one was non-viable, delegates would change their minds, shift their votes to more viable candidates, form alliances, make deals, spread lies and gossip, and — ultimately — the delegates would elect a single presidential candidate.

There was one consistent rule that was always followed in the Republican party, which guided everything else about the convention: to be the official presidential nominee, you couldn’t just win the most votes on a convention ballot. You had to win an outright majority of the votes. Otherwise, you’d keep voting until someone reached 50%+1. (The Democrats set the bar even higher: until 1936, they required two-thirds of the delegates to agree on a single nominee.) It was a pretty good process: this system nominated Abe Lincoln (after four ballots), Calvin Coolidge (one ballot), Dwight Eisenhower (two ballots), Barry Goldwater (one ballot), and F.D.R. on the Democratic side (four ballots)… often after electoral “floor fights” between different party factions represented at the convention, which had to be resolved with compromises.

However, in the 1970s, the Democrats became fed up with the way the process gave “party bosses” a lot of influence, since they were often elected as delegates and they were often the ones who ended up in “smoke-filled rooms” during deadlocked nomination fights making compromises and cutting “back-room deals” in order to get consensus on a single nominee. This frustration came to a head in 1968, when the Democratic party nominated pro-Vietnam Hubert Humphrey instead of anti-Vietnam Eugene McCarthy… despite the fact that primary polls (which were not binding in any way) showed 80% of the Democratic Party wanted an anti-Vietnam presidential candidate. There were violent protests surrounding the 1968 convention, largely as a result. To avoid future embarrassments, in 1972, a Democratic committee of liberal-progressives led by George McGovern gutted the 150-year-old caucus system in favor of a new innovation: binding presidential primaries. The national convention still happens, and delegates are still elected by the states, but there is also a direct presidential primary in each state. The delegates from each state are required to vote for a certain candidate based on the results of those presidential primaries. These bound delegates must swear an oath to vote for a specified candidate, and can face serious sanctions if they violate that oath.

For some reason, which I’ve never really understood, the Republicans decided to copy these Democratic reforms, even though they were put together by avowed liberal-progressives to increase direct democracy and decrease republicanism in the presidential election process — which is sort of the opposite of what the Republican party is theoretically about. So, during the ’70s, the Republicans mostly dismantled their caucus system and replaced it with a primary system very similar to the one used by the Democrats.**

That brings us up to date.

Ever since the “McGovern reforms” of the 1970s, the Republican nominee for president has been chosen, effectively, not by debate and discussion and compromise among well-qualified elected national delegates, but by direct popular elections. Because the results of those elections are known months in advance of the national convention, the process of negotiation also plays out months in advance of the election: candidates withdraw when they realize that they aren’t going to win. Soon, the party coalesces around a single candidate. By the time the convention rolls around, that candidate has won so many primary elections unopposed that well over half the national delegates are bound to vote for him. He is guaranteed to win on the first ballot. There are no more floor fights, because the outcome is known from the beginning.

Thus, modern national conventions have gone from being the most interesting events in American politics, where anything can happen, to the most boring — simple rote coronations. They inevitably play out like this:

- During the primary season, the Republican party holds a series of state primary elections, where roughly 2,500 delegates to the national convention are selected and bound to a candidate.

- By the end of the primary season, one candidate gains sufficient momentum to “clinch” the nomination (more than half the delegates are bound to support the candidate, making opposition pointless), and so all other candidates withdraw.

- The Republican National Committee — a permanent organization that schedules the quadrennial conventions and manages the party between conventions — meets just before the convention and draws up a series of rules changes and platform alterations through various committees.

- When the convention starts, the delegates gather in the convention hall. They are officially certified as delegates by the Committee on Credentials and given a voting card.

- The delegates then vote (by simple majority, in a series of voice votes) to rubber-stamp everything the RNC decided in Step #3.

- When it comes time to nominate the presidential candidate, there is only one candidate left who meets the nomination requirements. Officially, there is supposed to be a formal vote, but, with only one candidate left, this can be (and usually is) dispensed with: rather than doing a tedious vote, all the delegates simply clap for the presumptive nominee, in a beautiful show of consensus and unity.

- The chairman of the convention bangs a gavel and declares, for the first time, that Candidate X is now the official presidential nominee of the Republican Party in Year Y. This is the legally binding moment at which the candidate becomes the Republican Party nominee, with all that entails.

- Finally, the climactic moment: the nominee gives his acceptance speech.

This is all supposed to be perfectly choreographed to make the event look good on television: everyone smiling, dissenters silenced or marginalized. (Republicans, it must be said, will merely cheat you. If you’re unlucky enough to be a dissenting delegate at the Democratic convention, you may get beat up, have a death threat phoned in against you, and be ejected from the convention, which is what they did to my mother in NYC ’92.) Everything about the convention is designed so the delegates just have to spend three days clapping, smiling, and making the party look good to reporters. The presidential nomination process, especially, needs to be finished exactly at 8 PM so the networks can most conveniently cover the acceptance speech. The people who run the Republican Party — the oft-reviled Establishment — generally want conventions to work this way, because they think it makes the “party brand” more “marketable” and helps the “healing process” after a sometimes-bruising primary battle while providing “earned media” to the nominee with his prime-time acceptance speech.

It almost always works out the way the Establishment wants. After all, the Establishment also designed the primary process to create maximum leverage for winning candidates. Moreover, by its very nature, the primary system helps ensure that (even more than the old caucus system), every delegate elected to the national convention is a consummate political insider, with very few rebels who might try to do something crazy, like radically reform the RNC or the party platform. The Establishment is thus able to control the entire process, from beginning to end, with little risk of resistance or even any surprises.

However, the core idea of the national convention is still there: it is still a gathering of elected delegates representing all the states and territories of the Union. It is still the technically the delegates, and not the primary voters, who select the next president of the United States. And it is still the rule that, to be nominated as the Republican candidate for President of the United States, it’s not enough to have the most votes. You have to have the votes of a majority of the convention delegates. If the Republican delegates meet at a national convention, have a presidential ballot, and nobody gets 50%+1 of the votes, then they’ll have to vote again, and keep on voting until somebody wins… just like the wild conventions of old. Since the McGovern reforms were instituted in the ’70s, though, this has never actually happened.

But: in 2016, a year with multiple candidates in the field, splitting the votes more or less evenly, where seemingly no candidate is on track to having a majority of the delegates bound to them before the convention, where both frontrunners (Donald Trump and Ted Cruz) are widely loathed by the party Establishment (which, as mentioned, has considerable control over the convention process), it is possible for the process to break down. Multiple candidates stay in the race. No one enters the convention with a “clinching” majority. The delegates refuse to rubber-stamp the RNC’s new rules. At that point, the modern Establishment script goes off the rails, and we start a real-live, old-school, floor-fightin’ national convention, with multiple votes, multiple factions, compromises, smoke-filled deal-making rooms, impassioned debates, dark horses, and more — all aired live, for the first time in history, on national television.

You can see why us political types start to salivate at the very idea.

So that’s the view from 10,000 feet on the Republican presidential nominating process. In our next post, we’ll drill down into the nitty-gritty of the current convention process, and start talking about how it might be manipulated by various interested parties in a closely-fought convention floor fight.

*This is a tad simplified, because the details varied across dozens of states over the course of 116 years. In particular, there was often an intermediate step between the local caucus and the state convention, called a district convention, which handled local party finances, chose local party candidates, and selected state delegates for the state convention.

**Three states (CO, WY, ND) still hold traditional unbound caucuses, and a few states (IA, ME, and MN most prominently) hold a bastardized version of the traditional caucus where delegate elections and a half-hearted presidential primary are combined in a single meeting.