Letters to a Growing Catholic #1

NOTE: This post was originally published at my Substack. The footnote links go there instead of to the bottom of the page.

My beloved daughter,

As you mature from a girl into a woman, you will naturally start to ask new questions about things that you have always believed. You will discover the answers to most of these by yourself, although I hope that your mother and I always be patient and eager to help. Many of your questions will be about small things, like how to be a good party host or why the economy sometimes has recessions or what in the world a boutonniere is. You will also have some big questions: Who am I? Why am I here? Where am I going? What does it mean to do good and avoid evil? We have given you answers to these questions from Jesus and the Catholic Church, but you will start to ask whether our answers are correct.

After all, when you look around the world, you see many people who believe many different things. We are Catholics, but some people are Jewish, some Islamic, some Hindi. There are a thousand flavors of Protestant Christianity, of course. The other Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox, dwarfs Judaism and every single Protestant sect. Materialist atheists, who believe that there is no God, no Heaven, and nothing in the cosmos except matter, make up a sizable and growing chunk of the U.S. population. All these religions (and several others) (although not as many as you might think) have different answers to those big questions: Who are we? Why are we here? Where are we going? What does it mean to do good and avoid evil?

So how can you know that your answers are right and their answers aren’t?

However, you are unlikely to encounter many actual Jews, Muslims, Hindus, or even Protestants. If anyone tries to actively evangelize you as you grow, it will most likely be a materialist atheist, and God bless them for trying to save your soul in their own funny way! But even they are fairly rare. The common religion in our country is very different. It is poisonous, not just to our Catholic religion, but to all sincere beliefs.

Let me give you an example.

A few weeks ago, when we were up at the cabin, I was floating on the lake with my book as usual, but the wind was strong and I had to give up on reading for a bit in order to keep my floaty close to the dock. I got to talking with one of our old cabin friends. (I won’t say which.) Our friend’s daughter has apparently started dating a Jew, and she is apparently doing this (among other reasons) because she thinks it will annoy her Christian mother, our friend.

Our friend sighed and shook her head at this point in her story and said, “Of course, it didn’t work.”

I, floating next to her, nodded thoughtfully, attempting to agree. “Oh, yeah, I’d take a serious Jew over the average Christian today, too.” (For reasons I’ll explain, I really do believe this. However, to you, I will add that it is still very far from the ideal.)

Our friend shook her head. “It’s not that. I told her, ‘It doesn’t matter, as long as he has faith.’ Who are we to say whether his beliefs are better or worse than ours, as long as he believes in something?” So our cabin friend doesn’t care what this young Jewish man believes. She cares only that he believes.

Our friend is a very normal American adult (and a perfectly average “Christian”). You will hear versions of this all the time, if you haven’t started hearing it already. I have seen variations on “As long as he has faith” and “Who’s to say our beliefs are better?” many times since my conversation at the cabin.

The average American considers herself a Christian, but is not a Christian. The average American follows a different religious system. Theologians and sociologists call it “indifferentism.” That is a fancy, Latin-sounding way of saying “doesn’t-matter-ism”. According to doesn’t-matter-ism:

- no religion is better than any other,

- all religions are equally valid paths to God or Heaven, and

- the only important things in life are to enjoy things while still being nice to people; the rest doesn’t matter.

In doesn’t-matter-ism, it doesn’t matter what particular religious beliefs you have, because you don’t actually believe your own “beliefs.” You go to Mass or mosque or whatever simply because it’s a family tradition, or because you “get something out of it,” or because you like the people, not because you think Jesus Christ was actually the Son of God or that Muhammed was actually God’s final prophet. To you, those details don’t matter—not really.

There are Catholic doesn’t-matterists, Muslim doesn’t-matterists, and agnostic (even atheist) doesn’t-matterists. They think they belong to different religions, but they all believe exactly the same things about who we are, why we are here, where we are going, and what it means to do good and avoid evil. Specifically, they think (surprise) it doesn’t matter, because things will all work out for the best (as long as you’re nice). The differences between how they pray mean no more to them than the differences between how Italians and Mexicans make pizza. For them, religion is just there to be beautiful and make you feel happy and remind you to be nice to people.

Doesn’t-matterism is the dominant religion of American society. “It doesn’t matter, as long as he has faith.”

This is a pretty strange idea, when you think about it.

If you, someday, bring home a perfectly lovely young man who is very kind in every particular, but who believes with all his heart that the Sun revolves around the Earth (even though we know, from science, that the Earth revolves around the Sun), I would find that very weird. I might regard it as a simple eccentricity, since heliocentrism very rarely impacts your daily choices. But it would be still be weird, even if I let it go.

On the other hand, if your beau believed that the only path to a healthy life was by getting infected by a tapeworm once every few months (because “the tapeworms consume your negative ions, which prevents your heart-protective antioxidants from going out of balance”), I would be concerned, because I think tapeworms are dangerous, and his contrary beliefs could have a very big impact on your daily life. Still, I’m no doctor, so I would hear out his pro-tapeworm arguments.

My concern would escalate to alarm, however, if I mentioned my concerns to you and you replied, “Oh, Daddy, who cares what he believes about health as long as he has beliefs about health?!”

These beliefs about tapeworm-based health care are either true or false. I strongly suspect they are false, but I could be wrong. What I know for certain is that it matters whether they are are true or false. If he routinely ingests tapeworms, and you marry him and start ingesting tapeworms to “celebrate his beliefs” or to keep the peace or to set a “good example” for your tapeworm-eating kids, but his beliefs are false, then you will be sick and unhappy a lot of the time (because you’ll be full of tapeworms). You could even die! I care very much what your future boyfriends believe about health, not just whether they have beliefs about health—and pretty much everyone agrees with me! This stuff is serious!

Yet when we come to the most important questions of all—the questions that define for us how we live, how we die, and why any of it matters—many of our well-intentioned neighbors adopt a cold indifference. “It doesn’t matter, as long as he has faith!” I think our friends are just trying to be nice. By minimizing their differences, they avoid having to disagree with their friends about important beliefs, and they avoid having to worry about whether their friends are living good lives. That’s nice, right? But it is not kind. It is not honest. It is not human.

Humans (if you ask me) are made to believe true things and reject false things. The truth matters.

This is the nature of the world in which we live, which does not give two farts about whether you believe tapeworms are bad for you. Tapeworms are bad for you whether you realize it or not. Our world has many such dangers. We must learn the difference between true and false just to thrive in our dangerous world. Even babies learn real and not-real long before they learn the difference between good and evil.

Believing true things is not just a survival trait in nature; it also our nature, our human nature. Humans were designed by a good God to know and love the truth. Ultimately, He wants us to know, to love, and to serve the Truth, capital-T (which is God Himself). People who believe even the smallest falsehood (which, to be fair, is all of us) are impeded from this, our ultimate purpose. People who believe false things therefore cannot live as freely and as fully as people who believe true things. They are, in other words, unhappy.

Even if someone settles into complacency with a comforting lie (or even a dubious truth!), there is always an unsettling whisper, deep down, that reminds him: “You know better. You know this isn’t right.” It’s like the Adventure Time comic where Finn, Jake, and Ice King end up in the illusion-world created by the Lich:

You may recall (it was a long time ago) that everything in that illusion world was actually Lich-bugs, and our heroes were all being anesthetized so they could be eaten alive. Finn and Jake’s pursuit of the truth, although painful, was heroic. Our happiness, right now, today, depends on whether we are chasing the truth (wherever it might lead us), or hiding from it. The more important the questions are, the more our happiness depends on our quest for the truth. And there are no questions more important than the religious questions.

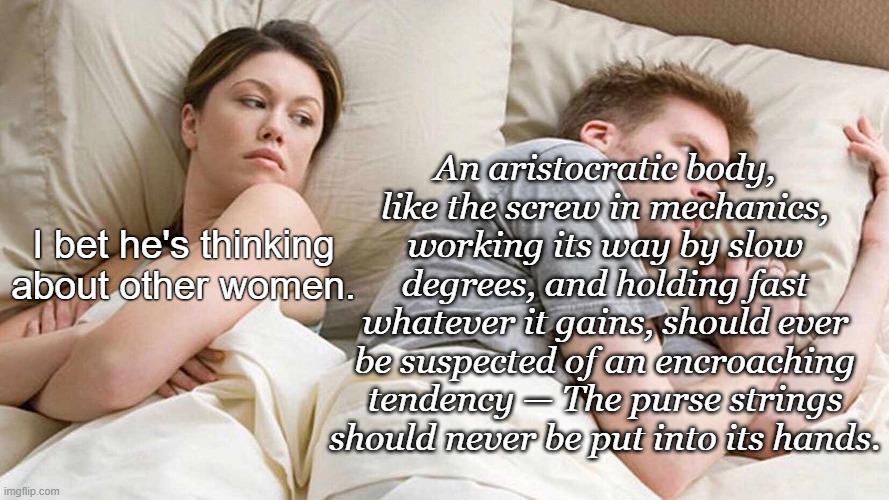

Religions themselves do not usually come out and embrace doesn’t-matterism. (A lot of mainline Protestants tried it, and now there are a lot fewer mainline Protestants.) Religions know that the truth matters. They are on fire for the truth (as they understand it); that’s what makes them religions. That’s why I find it much easier to respect and agree with a serious Orthodox Jew than a doesn’t-matterist Catholic. The Jew is playing for a different team, but at least he’s playing the same game. At least he cares about believing truth and avoiding falsehood!

Yet religious people have their own ways of hiding from uncomfortable truths, and I’m sorry to say that this includes many Catholics (although not Catholicism itself).

Many religious people are afraid they are wrong about the most important questions of their lives. Actually, let me rephrase that: every sane person is at least a little bit afraid that they are wrong about the most important questions. They want to protect themselves from that possibility.

There are good reasons for this fear. If we ever find out we are wrong about the big questions, then we have to change a great deal about our lives. If you learn that Christ did not rise from the dead, then you should stop being a Christian. That’s not my opinion; that’s Christian doctrine: “If Christ is not risen, then our preaching is in vain, and your faith also is in vain.” (1 Cor 15:14) But many of us have put down roots in our church communities, as friends and volunteers. We have set up our lives and our relationships around our beliefs. We choose our vocations based on our religion, marry people who share our religion, and raise our kids in our religion. (Everyone does all these things, even atheists and doesn’t-matterists.) So wouldn’t turning away from our religion destroy everything that is good in our lives? Wouldn’t it be better not to know? This is a reasonable fear! (I will have more to say about the usefulness of this fear in my next letter.)

There are also bad reasons to fear. Religious people, in particular, are often afraid that God will punish them severely for believing the wrong things, or even for having doubts. I have known many Catholics who think that their religious duty is to prevent their minds from even thinking thoughts that are contrary to Catholic teaching—or, at least, their understanding of Catholic teaching. (Their understanding is usually pretty bad, because they are so afraid of asking questions about it!) This aversion is not how the Catholic Church actually understands faith, doubt, or the motives of credibility, but enough people think it is that they are terrified of asking questions or (worse) getting unsatisfying answers.

If you give into these fears, hiding from your own best understanding of the truth because you fear the consequences of admitting it, you only doom yourself. Your doubts and fears will grow and grow, harder and harder to keep locked in a closet, until finally they burst out and swallow you whole. By that point, they won’t even have to fight you. By locking them away, you will have given them all the strength they need to sweep you away from everything you believe in—even if, in reality, your beliefs were true but you were just too scared of exploring them to find that out. There are many people in my prayers these days who followed just this path on their road out of the Catholic Church.

You must pursue the Truth wherever it takes you, even when it comes to the big questions of life, the universe, and everything. That is what you have been made for. I strongly and deeply believe that, followed honestly and to its conclusion, that journey will always bring you home to the Catholic Church and closer to God—yes, perhaps after some churn in the rapids—because that is where the Truth has always taken me.

We should model ourselves after the Apostles. All of them were Jews (some devout, others not) who believed normal Jewish things. Then along came Jesus, who promised to make them “fishers of men” and who had many strange sayings about the Sabbath and the Kingdom of God. Many departed, because they refused a Truth they found too strange to accept, but the Apostles, zealots for Truth, remained. “Lord, to whom else would we go? You have the words of eternal life.” (John 6:68) At first gradually, then all at once, the Apostles were not quite Jews anymore. They converted to the true faith because they were not afraid of chasing the Truth where He led, even as He led them across stormy seas and unimagined trials.

We worship a God who Is Truth itself, whose very Incarnation is the logos, the true Word. Never fear the truth, because, in fearing it, you fear Him. You can be certain that you will never be damned for following your conscience after doing your very best, to the limits of your Earthly ability, to honestly and humbly inform it. You need only fear surrendering to the gentle anesthesia of America’s ambient doesn’t-matterism. Embracing doesn’t-matterism would protect you from many conflicts, but it could not possibly be true, because these questions—who am I? why am I here? where am I going? what is good?—matter more than anything else in the world.

Love,

Dad