Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In this series, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed at improving the structure of the U.S. national government, without addressing substantive issues. Today’s proposal:

AMENDMENT XXVIII

A two-thirds majority is not required to override a presidential veto.

As a result of this amendment, the relevant paragraph of Article I, Section 7 would be revised to read as follows:

Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration

two thirds ofthat House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved bytwo thirds ofthat House, it shall become a Law.

I put it to you that the central problem in the American system of government is that Congress is broken.

Congress is (according to the Constitutional plan) the branch that makes the laws, the branch that sets all non-emergency policies (through laws, through the power of the purse, through its power to issue debt, through its power to declare war), and the branch that exercises the most direct and effective oversight of the other branches (not to mention the other house of Congress!). This is because Congress is the branch that most directly represents the interests and will of the voters, who are the ultimate source of authority for the entire system. All our branches of government are equal, but the Founders also clearly designed Congress as first-among-equals.

Congress is (in reality) the weakest branch, least-among-equals. Most laws are made by the executive branch through the regulatory process, or by the judicial branch through creative “interpretation.” Congress is unable to pass laws of its own, and routinely struggles to have its laws followed when it does. Congress is a squib, a spent force, the fundraising arm of the two-party system, a soundbite theatre, a Twitter trending topic… but it isn’t a legislature, and has not functioned as one for some time.

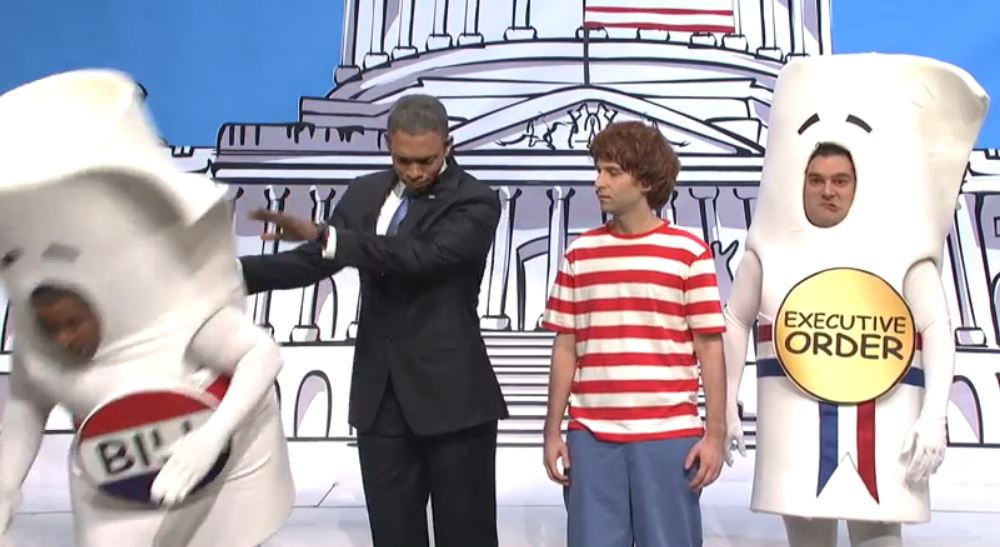

The power vacuum left behind by Congress’s collapse has been filled by what pretty much everyone now calls The Imperial Presidency. The term was somewhat facetious when it was coined. It grows less facetious every year, as the Presidency grows annually to more closely resemble a monarchy–and not the charmingly impotent Elizabeth II kind! The Supreme Will of the President (exercised through clever technical abuses of overbroad statutes and legal tricks to delay or prevent judicial review) is increasingly the central governing principle of the United States. We’re maybe a generation from the President just donning purple and calling himself senatus princeps, if you know what I mean.

There are many reasons for this, and we will likely return to Congress’s brokenness and our modern Emperor-President many times in this series.

(Gerald Ford and the neo-reactionaries will cry, “No, it’s the imperial bureaucracy!” They have a point. We’ll come to that in future installments. For purposes of the presidential veto’s malodourous effect on the separation of powers, there is no relevant difference–and it’s worth noticing that, just like today, the collapse of the Roman Republic coincided with the exponential expansion of the Roman imperial bureaucracy.)

One important cause of Congress’s ennervation (and the Executive’s consequent empowerment) is the presidential veto.

The Founders conceived of the presidential veto for some charmingly quaint reasons. Federalist #73 (by Alexander Hamilton) explains:

The propensity of the legislative department to intrude upon the rights, and to absorb the powers, of the other departments, has been already suggested and repeated; the insufficiency of a mere parchment delineation of the boundaries of each, has also been remarked upon; and the necessity of furnishing each with constitutional arms for its own defense, has been inferred and proved. From these clear and indubitable principles results the propriety of a negative, either absolute or qualified, in the Executive, upon the acts of the legislative branches. Without the one or the other, the former would be absolutely unable to defend himself against the depredations of the latter. He might gradually be stripped of his authorities by successive resolutions, or annihilated by a single vote.

In other words, the presidential veto power is necessary, because otherwise Congress might gobble up presidential powers, even in violation of the Constitution. Hamilton is writing this, remember, several years before Marbury v. Madison would establish the Supreme Court’s formidable powers to defend the other two branches against attacks by the third.

Furthermore, Hamilton tells us:

But the power in question has a further use. It not only serves as a shield to the Executive, but it furnishes an additional security against the enaction of improper laws. It establishes a salutary check upon the legislative body, calculated to guard the community against the effects of faction, precipitancy, or of any impulse unfriendly to the public good, which may happen to influence a majority of that body.

Early in the Republic, the veto was used in this way: pretty rarely, pretty cautiously, and only to protect the Constitution or the prerogatives of the other branches, not to interpose the President in the legislative process.

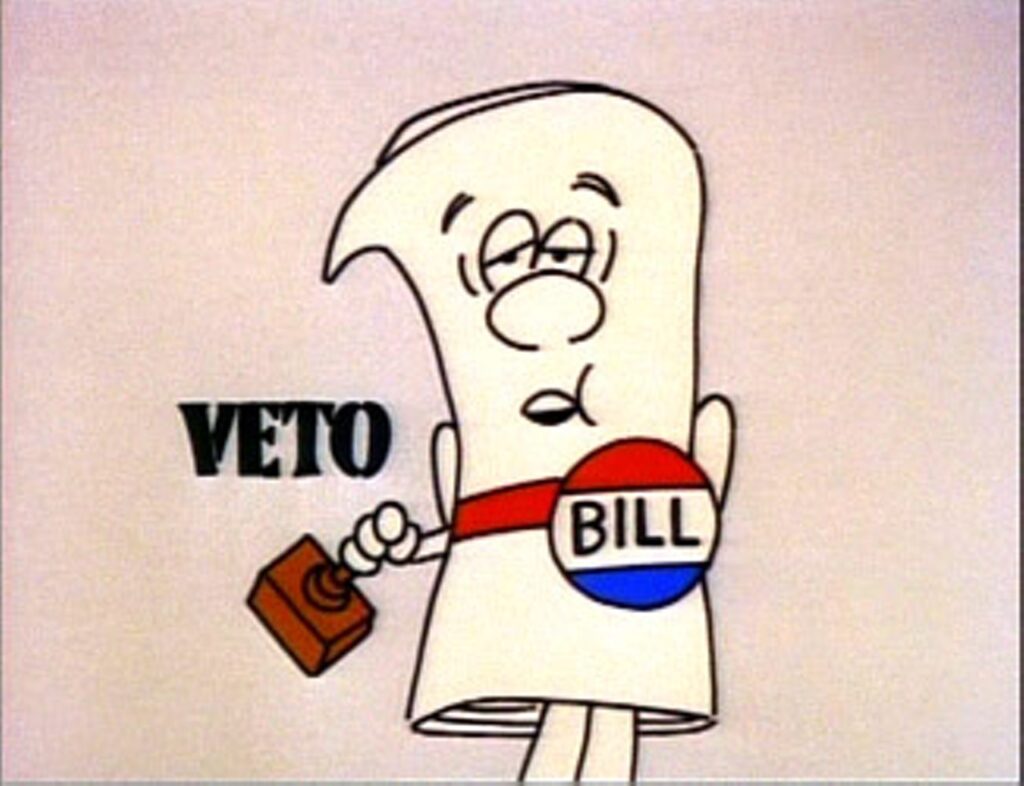

Here is how the veto is actually used today:

(1) Sanctifying Abuses of the Law

When the President uses the powers Congress gave him to do something Congress did not intend and actually opposes, Congress often tries to fix it by passing a new law against it. The President, who enjoys exercising those powers Congress is trying to block, vetoes the new law. As long as the President can get the support of at least one-third of either house of Congress, he wins. Congress loses a little of its power to set the laws of the land; the President gains a little.

Headcount-wise, it is easier to impeach and convict the President of the United States than to override a presidential veto. Impeachment requires a majority in the House and two-thirds of the Senate. A veto override requires two-thirds in both. So if you really hate a certain presidential veto, and you’ve got the majority of Congress on your side, but you’re a few votes short of two-thirds in the House, the really smart and ruthless legislative party will impeach and convict instead. Those are the incentives we’ve set up.

(2) Squelching Embarrassments

When the President does something flagrantly illegal, but Congress supports him, Congress occasionally tries to fix it by passing a new law supporting it. The President, however, is embarrassed to admit that he has violated the law, and worries about the bad press he will get for needing to be “bailed out” by Congress, so he announces his intent to veto it and encourages the most loyal members of his own party to vote against the bill. (Sounds weird, but it’s word-for-word what happened with H.R. 2667 in 2013.) This leaves Congress with three options: it can hope someone else sues the President and wins, because Congress generally cannot sue the President; or it can impeach the President and remove him from office; or it can surrender, losing a little of its power to set the laws of the land, while the President gains a little.

(3) Getting Broad Powers While Evading Review

There are a lot of provisions in federal law that allow Congress to cancel certain extraordinary exercises of executive power. For example, the Congressional Review Act allows Congress to, by joint agreement, block problematic executive-branch regulatory laws from going into effect. The National Emergencies Act allows the President to declare national emergencies and take on emergency powers, but also gives Congress the ability to rescind those emergency powers by a joint resolution. The Immigration and Nationality Act gave the President the authority to cancel deportation procedures at his discretion, but gave Congress the power to override that discretion. The War Powers Resolution gives the President the authority to start a war without a Congressional declaration of war (as required by the Constitution), but gives Congress the power to stop any such war on review.

In theory, these provisions all give Congress a way to keep the Imperial Presidency in check, by giving broad and flexible powers to the president but allowing Congress to review and restrain the exercise of those powers.

In practice, however, whenever Congress passes a joint resolution cancelling a presidential action, guess what? The president vetoes it! Then he laughs in Congress’s face. The Supreme Court confirmed in INS v. Chadha (1983) that the presidential veto power applies to all exercises of legislative power, including these Congressional reviews. This ruling was, in my view, the correct legal ruling given our current Constitution. (That’s why I’m saying we should change the Constitution.) Remember when President Trump declared a “national emergency” in order to try to build his border wall? Congress voted to cancel that emergency… but, because they could not break Trump’s veto, it remained in force for the rest of his term.

Eventually, because it was obviously pointless, Congress more or less gave up even trying to disapprove presidential actions. The President gets to keep the broad and flexible powers Congress gave it, but Congress lost the ability to review and restrain those powers (which it was really counting on when it handed those powers over in the first place).

(4) President as Legislator-in-Chief

The Founding Fathers did not foresee the rise of political parties. In fact, they were terrified of political parties, because they knew that strong political parties would break their design of the Constitution. They weren’t wrong!

The Founders expected government officials would be loyal to themselves first, their branches second, and the American people third. A lot of our checks and balances are based on the idea that elected legislators and elected Presidents have few common political interests and are mutually jealous and suspicious of each other.

Political parties spoil this assumption. In fact, the President has strong political ties and shared interests with certain members of Congress, and vice versa. Loyalty to the party and the party agenda comes way ahead of branch loyalty, and sometimes even trumps loyalty to one’s self. (Just look at how Bart Stupak and the Blue Dog Democrats knowingly immolated themselves on the pyre of Obamacare, which was unpopular at the time, was definitely going to cost moderate Democrats their seats, and effectively wiped them out.)

The presidential veto makes him the single most powerful force the entire legislative branch. Wielding the veto, one single man, not even directly elected by the people, can prevent Congress from acting on any legislation, for any reason, until it meets his exacting conditions–or the conditions demanded by his political party. The President is, for the most part, able to dictate laws to the legislative branch… and, since before the beginning of living memory, that’s exactly what the President has done. The impossibly difficult veto overrides were few and far between a century ago… but they have become even fewer now, because the President wields ever-growing power within his party to punish any sitting legislator of his party who dares oppose him. (We’ve had two impeachment trials in the past four years, and we’ll likely have another if Republicans retake the House in 2022, albeit all unsuccessful. The last successful veto override? July 15, 2008, over thirteen years ago.*)

The results? Obvious: it is impossible to pass major domestic legislation in this country without a “trifecta”: single-party control of the House, the Senate, and, above all, the White House. This happens once a decade or so. (The other eighty percent of the time is spent in unbroken legislative gridlock.) The President then supervises members of his party in Congress in crafting a bill that is acceptable to “his” majorities in both houses without compromising his own re-election chances. Do I really need to attach links to sources for this, or have you all paid attention to at least one major piece of domestic legislation on at least one occasion in the past twenty years and therefore know how this works?

This assertion of control over the legislative process is, by far, the most important and common use of the veto today. (It is almost never actually exercised; an official White House veto threat is usually enough.) What a sad inversion! The Founders were afraid that, without the veto power, the Congress would swallow the executive branch and “the legislative and executive powers might speedily come to be blended in the same hands.” But, thanks in part to the veto power, that’s precisely where we’ve arrived… but with a monarchical presidency blending the powers, not the democratic-republican Congress!

(5) Ever-Deepening, Self-Sustaining Gridlock

The presidential election then, predictably, devolves into an extended debate about domestic policy… which is something the President, in our system, should not have any significant authority over in the first place, nor even any opinions save what he reports to Congress in his annual State of the Union letter (not speech) about how to improve the efficient functioning of the People’s government established by Congress. Since the presidential election ends up being about legislation rather than competence and good judgment (which is what presidential elections are supposed to be about), we end up with deep partisan polarization around whoever happens to President… which makes bipartisan deal-cutting even more difficult, because any bipartisan deal has to be made, first and foremost, with that president, the legislator-in-chief, and the despised enemy of the opposition’s entire voting base. What do you get? Gridlock! (And a lot of italics for emphasis.)

Rather than the People voting for Congress to enact an agenda and for a President to competently administer the government, the People vote for a President to enact an agenda, Sir Humphrey Appleby administers the government, and Congress sends out fundraising emails telling you that they need YOUR HELP TO STOP THE [opposition party’s] ATTACK ON GRANDMAS AND FREEDOM ITSELF. The People become demoralized and frustrated when this convoluted, wasteful system–which is essentially unworkable even at a small scale, but absolutely unworkable given our titanic federal government–fails to work and does not produce the results they voted for.

The veto does little good and much evil. Both parties can point to one or two cases where the veto delayed legislation they opposed for several years, but both parties can also point to dozens of cases where even a merely threatened veto strangled good legislation in its crib. So get rid of it!

The Good Parts of the Presidential Veto

AMENDMENT XXVIII

A two-thirds majority is not required to override a presidential veto.

You probably noticed that my proposed amendment does not actually get rid of the veto. All it did was get rid of the two-thirds override requirement. Everything bad about the veto comes from the fact that Congress has to come up with extra votes in order to ignore it. If Congress could simply vote again to bypass a veto, the veto is no longer a problem.

But why should it have to go through that rigmarole? The process set out by the Presentment Clause requires Congress to formally deliver a bill to the President, who then has ten days to veto it, which bounces it back to Congress, which then needs to schedule votes in both houses… the whole affair could easily take two weeks (allowing, among other things, pocket vetoes). Knocking out the two-thirds requirement makes this whole creaky, time-consuming process redundant, doesn’t it?

I don’t think so. The Founders were right, after all, about this: “faction, precipitancy, [and] any impulse unfriendly to the public good” may occasionally overtake Congress, especially in moments of great fervor and hurry. The Presentment Clause provides a cooling-off period before a passed bill becomes a law. The Veto Clause–even after my amendment gelds it–will still allow the President to send a bill back to Congress with objections, essentially saying, “Are you absolutely sure?” Overriding that veto will no longer be an impossible task for the President’s opponents… but it will force them to think a bit about whether they are really sure this legislation is a good idea.

This is often useful. Very often, an executive will recognize problems with implementing a bill that the legislators didn’t foresee, or didn’t fully understand. The executive’s warning can lead them to make useful changes, or simply reconsider a possibly-rash course of action, even if the veto is not binding. You can see this in cases around the country, where an executive veto plus a few days’ thought caused bills originally passed by veto-proof majorities to suddenly lose that support. I think this serves as a useful check on the legislative branch, in most of the ways the Founders expected… but without centralizing legislative power within the person of the President.

This “are you absolutely sure?” function is considered useful enough in England that it is the primary function of the House of Lords. Anything the House of Commons wants to become law will become law. The Lords’ sole function is to scrutinize each bill the Commons passes and offer advice on how the Commons can make it better (or why the Commons should get rid of it). They have explicit powers to delay legislation. And they can force the Commons to reconsider legislation. But they cannot block legislation outright. This has served both the Lords and the United Kingdom pretty well, which is why I’d like to see it continue in the United States.

For that reason, I think we should get rid of the two-thirds override requirement, but otherwise keep the presidential veto. Don’t erase it. Just geld it.

*UPDATE 4 October 2021: This article originally stated that the last veto override occurred in 2008. While veto overrides are very rare, they aren’t quite that rare. President Trump and Obama suffered one successful override apiece, in 2016 and 2021, respectively. The error was entirely mine.