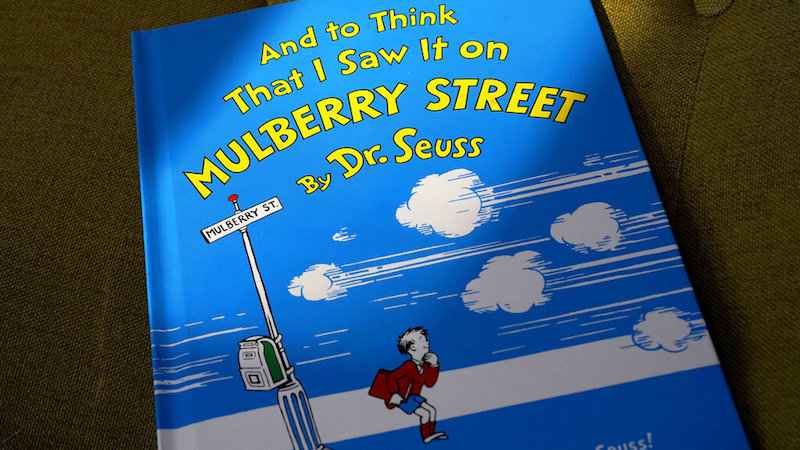

By order of his estate, six Dr. Seuss stories got cancelled this week, including the famous And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, first published in 1937. They are no longer being published and were subsequently banned from eBay for being offensive… unlike Mein Kampf, which remains available on eBay.

This controversy shouldn’t even be possible, because Mulberry Street — along with nearly all of the books swept up in this publication purge — should have entered the public domain in 1992.

Under a sane copyright regime, like the one the United States inherited from England and maintained for most of its first 150 years of existence, copyright terms last 10 to 20 years, renewable to a maximum of 40, maybe 50 years. Even with Dr. Seuss’s vigilant copyright renewals, Mulberry Street should have been public domain by about 1977.

Under a not-quite-sane-but-okay-I-can-see-it copyright regime, copyright lasts about that long OR for the life of the author, plus however long it takes for the author’s minor children to reach adulthood (whichever is longer). This ensures that the author is able to enjoy the fruits of his labor and support his family with it for his entire life. Seuss died in 1991, so copyright on Mulberry Street would have expired in January 1992. Nearly all of his books, including all the books swept up in the cancellation purge last week, would have entered the public domain by 2010.

Under the copyright regime in force at the time Mulberry Street was published — still a pretty sane one — Mulberry Street would have had a maximum of 56 years of copyright protection. It would have entered the public domain in 1993.

We retroactively extended that copyright law several times in the 20th century, ultimately extending Mulberry Street‘s copyright protection to 95 years. It will actually enter the public domain in 2032 — 40 years after Dr. Seuss’s death.

It would be even worse under the most modern laws, which keep works under lock and key for the life of the author plus 70 years. If Mulberry Street were published under today’s copyright laws, it would have been published in 1937 and not released to the public domain until 2062 — 125 years after publications.

Most works do not even survive that long. They are irretrievably lost to neglect while waiting to enter the public domain. Most old videogames, for example, are today preserved by archivists who operate in absolutely blatant breach of copyright law, hoping the copyright owners won’t mind protecting and emulating games produced for the Sega Genesis. Under my regime, Genesis games would have started entering the public domain around 2003 and the last of them would be released to the public right about now. However, under current actual copyright law, they are all copyrighted until the early 22nd century. A genuinely unthinkable amount of 1930s and 1940s films have been lost because copyright holders didn’t preserve them and others lacked the right to copy and protect them.

The Constitution grants Congress this power:

“to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing, for a limited time, to authors and inventors, the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

Long copyright terms are bad because they imprison important cultural touchstones in the hands of private actors for (right now) literally centuries. But they are also unconstitutional: they last long after any further “progress” might be “promoted,” and far beyond any “limited time period,” according to the original public meaning of that phrase. The Supreme Court decided in 2003’s Eldred v. Ashcroft that the Supreme Court cannot unilaterally decide where that line can be drawn, and fair enough. But we, the voters, should hold Congress accountable for driving a stake through the heart of this constitutional provision.

…and, as a direct result of this robbery of the public trust, Congress has now also allowed private actors to drive a stake through the heart of several beloved children’s classics.

If you’re mad about Dr. Seuss, fix copyright law.