Actually no Dobbs today. It’s all Whole Women’s Health up in here.

NOTE: This post was originally published at my Substack. The footnote links go there instead of to the bottom of the page.

I dashed this off in about an hour after whatever happened today in Dobbs v. Jackson and/or Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson (different Jacksons, mind!). Didn’t really check for typos, certainly didn’t bother with many links. That might be is a theme of my Dobbs coverage this year.

Even though I wrote this update quick, I spent most of the day trying to figure out the Court’s opinion in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson.

I mean, not really, the opinion itself was easy enough to read, it’s written in English, and the issues discussed are straightforward if you’ve been following the case, but what the decision’s effect is going to be, and why it was so emotional… this was not so clear.

In Whole Women’s Health, an abortion clinic1 determined that Texas’s SB.8 law (which forbids anyone from assisting in an abortion once the child has a heartbeat) violates the legal rights of Texas mothers to abort their offspring. Normally, when the state passes an unconstitutional law, you have two choices:

- Violate the law, wait for someone to enforce the law, then sue whoever’s enforcing it. This is the traditional approach, and it is often the only approach possible. The downside of this approach is that, if you lose the lawsuit, guess what, you’ve broken the law and now you’re going to be punished for it. Yikes. Are you sure you’re going to win that lawsuit?

- Don’t violate the law. Pre-emptively sue to stop the law going into effect. You can’t sue the state directly, because the Eleventh Amendment says you can’t sue states. But, the Supreme Court held in a (somewhat, ah, creative) 1908 case called Ex Parte Young, you can sue state officials who are responsible for enforcing the law—usually the attorney general—and the courts can then order the attorney general not to enforce the law. Upside: it’s much much easier to sue states for violating the Constitution (which they routinely do, let’s face it). Downside: it’s a semi-nonsensical constitutional hack. (Brought to you by Chief Justice Melville Fuller, who also helped give you Plessy and Lochner! What a guy!)

Texas’s SB.8 was extra-sneaky about this. It banned assistance with heartbeat abortions… but it also banned any state officials from enforcing the law in any way. Instead, the law could only be enforced by private citizens bringing private lawsuits. This was intended to get around Ex Parte Young and prevent pre-enforcement challenge.

Then, Texas loaded up just a ton of one-sided courtroom advantages for any private citizens who did bring lawsuits, awarding them money for winning (but not costing them anything if they lost); creating new, extra-strict interpretations of federal abortion precedents; allowing defendants to be sued multiple times by multiple plaintiffs for the same abortion; and so on. The law makes it very easy for plaintiffs to sue abortion providers, but very hard for abortion providers to defend the suits (and very easy for them to go bankrupt even if they win the suit). The purpose of this was to make abortionists think very, very hard about taking the risk of violating the law, even if they’re 95% sure they’ll ultimately win.

In short, Texas attempted to outlaw heartbeat abortions in Texas. They could have done this much more simply (by passing a law saying “heartbeat abortions are illegal and you’ll go to jail if you perform one”), except Texas had to bypass the Supreme Court’s decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which both say quite clearly that Texas cannot outlaw heartbeat abortions without violating the Constitution. (Those cases are, of course, nonsense, but a lot of the nonsense the Supreme Court emits is nevertheless considered binding law, and Roe/Casey are no exception.) The bizarre structure of the Texas law is intended to prevent judicial review. It is fair to say that Texas attempted nullification of Roe/Casey—except, unlike John C. Calhoun (who simply asserted state power to ignore federal law), Texas attempted to nullify Roe/Casey the legal way, by carefully tiptoeing around the judiciary’s jurisdiction. This was brilliant, novel, life-saving on a large scale, and quite dangerous to our constitutional order as it currently exists.

“Dangerous?! How?!” Well, imagine the State of New York wanted to cancel all public Catholic Masses in New York City indefinitely. This shouldn’t be hard to imagine; they did exactly that just last year, on what certainly, to me, looked increasingly like a pretext about public health, and their rules were such that (had they been upheld), as far as I know, some churches would still be closed today. Last year, the Catholic Church sued the Governor (not the state, you can’t sue a state) to stop enforcement of this law, and they won an emergency injunction. But suppose New York had used something like SB.8 instead: they don’t directly order any churches closed, but they instead make a rule that anyone who facilitates a Mass (the priest, the organist, the extraordinary ministers, the bishop, everyone) can be sued by any private person. And then New York puts its thumb on the scales by creating one-sided attorney fees, generous rules about venue selection, multiple lawsuits, and so forth. According to the logic of the Texas law, there’s nothing the federal court systems can do about this! This structure doesn’t just target the abortion “right”; it could be used to effectively destroy black-letter constitutional rights as well!

Whole Women’s Health (and most other Texas abortion clinics) were not willing to risk the stacked deck of a post-enforcement challenge on this one. So they instead suspended their abortion operations and then sued… well, they sued, like, a whole lotta people. They sued the attorney general, they sued a random state-court judge (even though Ex Parte Young says specifically you can’t sue state judges), they sued a random state-court clerk, they sued a private pro-life guy named Mr. Dickson (even though Dickson signed an affidavit insisting he had no plans to bring an SB.8 lawsuit), and they sued a bunch of officials involved in state medical licensing.

After oral arguments in Whole Women’s Health v. Jackson, I was pretty convinced that the Supremes were convinced of the danger and were going to puncture Texas’s balloon. I said that the Supremes were going to find some way to let the abortionists sue someone over this law. I didn’t know how they were going to do it without mangling Ex Parte Young, but I was pretty sure they would. And, once that happened, I said, it would be over pretty quick for SB.8, because SB.8’s whole trick is avoiding judicial review. Once it gets judicially reviewed, Roe/Casey kill it dead, fast!

And, on the face of it, it looks as though I was right. The decision handed down today was technically an 8-1 decision, in which the Supreme Court (Justice Gorsuch writing for the majority) agreed that, due to what amounts to a logical error in SB.8’s no-official-enforcement text, the abortion clinic could sue a handful of state licensing officials. (Justice Thomas dissented, maintaining that, sorry, pre-enforcement challenge of this law is simply impossible.) For what it’s worth2, I’m inclined to agree with Gorsuch, partly because his argument sounds right and partly because he’s such a stickler for particulars, even moreso than Thomas.

But the Supremes then split angrily about whether the Attorney General and state-court clerk could be sued under Ex Parte Young. (Roberts and the 3 progressives said “yes,” losing 5-4.) The three progressives would have gone further, striking down SB.8 in its entirety right here, right now, making whatever expansion to Ex Parte Young might be necessary. (Justice Sotomayor’s dissent is somewhat unclear on this point.)

I’ve been trying to wrap my head around that anger. Chief Justice Roberts is furious. Of course, he’s always furious when Gorsuch writes, they hate each other, but both dissents neglect the customary “I respectfully dissent” or even the less-respectful “I dissent,” and Roberts’ language in his closing is (by Roberts standards) jalapeno hot. At this point, I wouldn’t be stunned to see him retire this term in order to let President Biden replace him, because that’s how fed up Roberts seems to be with his right flank.3 But why be mad? They all agreed that the lawsuit can proceed! The rest is details!

Maybe not. (This is what held me up all day.) What exactly is going to happen when this decision goes allllll the way back down to the district court?

The district court judge in this case, Judge R. Pitman, is a solidly progressive Obama appointee, so I think this is straightforward (disclaimer – I am not a lawyer, just a nerd): Whole Women’s Health will proceed with the lawsuit against the licensing executives. Judge Pitman, exercising judicial review, will find SB.8 violates Roe/Casey, which it does. Roe/Casey are constitutional law decisions from a higher court that he has no choice but to obey. So he will enter a declaratory judgment stating, for the record, that the U.S. federal court system considers SB.8 unconstitutional and unenforceable. Then, building on the declaratory judgment, he will issue an injunction order against the licensing officials. The licensing officials will be directly barred from doing anything to enforce SB.8, and everyone else in the state will be put on notice that SB.8 is unenforceable in federal court. That should be sufficient for abortionists to resume aborting, once again shielded from justice by Roe/Casey.

Importantly, a judge cannot just enter a declaratory judgment for funsies; it has to actually do something in a live case within the court’s legitimate jurisdiction. That’s why it’s so important that the licensing officials can be sued. If they couldn’t be sued, then (according to the Supreme Court), nobody could be sued, and then there would be no case within the court’s jurisdiction, and no excuse to enter a declaratory judgment.

Here’s why I’m not so sure that’s going to be enough to let the abortionists get back to aborting: the declaratory judgment isn’t generally supposed to reach beyond the particulars of the parties before them. So Judge Pitman can draw whatever legal conclusions he needs to draw about the constitutionality of SB.8’s, insofar as it impacts state licensure, because the only defendants in the case are licensing executives. That should be enough to allow Pitman to write a judgment that shields medical doctors, nurses, and so forth from prosecution under SB.84.

But SB.8 applies to everyone who assists a heartbeat abortion (except the mother). The abortionist who does the abortion might be shielded, but what about the abortion clinic receptionist? That’s not a licensed job. What about the volunteer clinic escorts out front? What about the clinic janitor? All these people may be liable under SB.8, and SB.8 makes it very painful and expensive to find out in a court of law. Can Judge Pitman write a ruling that covers all those people under the shield of Roe/Casey as well? Can abortion clinics operate without all those people? And will whatever ruling Pitman writes survive the scrutiny of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is where the case goes after Pitman? (Note well: the Fifth Circuit is currently the most conservative court in the country, and has defended SB.8 in ways that even I didn’t expect at the outset of this case.)

I have no idea what the answers to these questions are. I am not a lawyer, and I have virtually no understanding of the procedural mechanics down at this level of detail. Josh Blackman thinks he knows, and he is literally the only person I found today, left or right, who talked about these mechanics in any kind of detail. Blackman thinks abortions will not resume on the strength of this ruling alone. Based on the vague but intense anger from left-wing legal commentators like Mystal, Millhiser, Vladeck, and Sacks, I think they agree. (That being said, a related lawsuit proceeding in Texas state—not federal—courts might eventually do the trick, regardless of what the federal courts do.)

If the U.S. Supreme Court (or at least Roberts and the progressives) don’t think this order is enough to grant effective relief to the abortionists in this case, that could explain their anger. It would make this decision something of a bait-and-switch, perhaps even a political ploy to avoid bad headlines.5

But they don’t seem to think that. Roberts6 and Sotomayor7 both say that they expect the district court to enter adequate “relief” for the abortionists. I don’t think they would have said this if they’d thought otherwise.

So whence the fury?

Here’s what I think this case is really, actually about. I don’t think it’s (directly) about abortion, and, deep down, I don’t even think this is about the procedural rules that govern the courts. I think this case has exposed a fault line on the Supreme Court that hasn’t been discussed seriously in living memory. I think this case is about judicial supremacy.8

There are two schools of thought on what role our judiciary plays in the federal scheme of government. I will call them the departmentalist view and the supremacist view.

Judicial departmentalists believe that the role of the judiciary is to decide cases and controversies that come before it. Which cases and controversies are those? They are defined in the Constitution:

In all cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction.

In all the other Cases… the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction… with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

So the Supreme Court can decide cases and controversies if they involve ambassadors, states, or public ministers, and any other cases where adverse parties interpret the law differently and Congress authorizes them to decide.9

For the departmentalists, the opinions of the Supreme Court and its interpretations of the Constitution are absolutely binding… within that sphere. Congress has made that sphere pretty big… but the departmentalists believe they cannot reach beyond that sphere and decide cases and controversies outside it. They rest their view on John Marshall’s opinion that “[i]f the judicial power extended to every question under the constitution” or “to every question under the laws and treaties of the United States,” then “[t]he division of power [among the branches of Government] could exist no longer, and the other departments would be swallowed up by the judiciary.”

For the supremacists, the judicial branch is the Constitution’s designated guardian of… the Constitution. They see the judiciary as the final backstop. Its mission? To protect the legal rights of all persons under U.S. jurisdiction from all other constitutional actors—even if it means bringing Congress, the President, or a sovereign State to heel. In order to accomplish this mission, the supremacists hold that the Court’s power of judicial review extends exactly as far as it needs to extend in order to vindicate the Constitution and protect all citizens. If Congress didn’t grant sufficient jurisdiction, then that’s just so much the worse for Congress, because the judiciary is an independent branch with independent authority to defend the law, and it’s not afraid to use it. They rest their opinion on the views of John Marshall: “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Indeed, “[i]f the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery.”

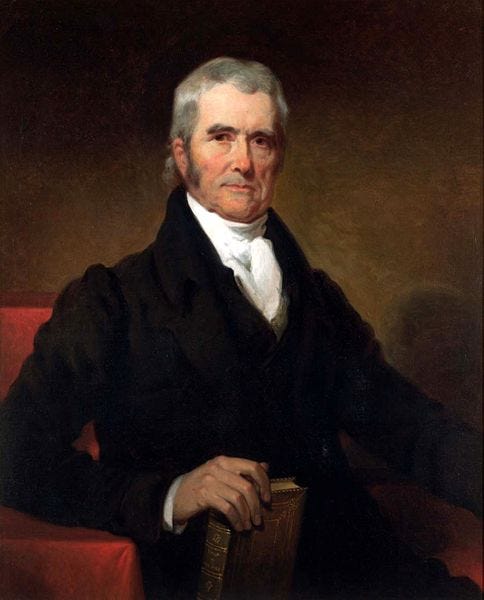

You will notice that both schools derive their contradictory conclusions from Chief Justice John Marshall. Oh, dear. Michael Stokes Paulsen tries to referee the competing claims about Marshall in the single most important article I’ve ever read, “The Irrepressible Myth of Marbury.”

Both schools have eminent supporters. Abraham Lincoln was a determined departmentalist. Stephen A. Douglas was a supremacist. That was what the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates were about. They were arguing over a Supreme Court decision you may have heard of: Dred Scott v. Sandford. Douglas (and the South) believed Congress had to obey Dred Scott and allow slavery in the federal territories, because the Supreme Court was the Supreme exponent of the Constitution. Lincoln (and the North) believed that the Dred Scott decision affected Mr. Dred Scott and Mr. Sandford, but did not bind Congress. Lincoln vowed that, if elected, he would ignore Dred Scott’s order to allow slavery in the territories. The South (which believed in judicial supremacy) believed the North was abandoning the Constitution, so they seceded. In other words, this debate caused the Civil War.

Weirdly, the North won the war but lost the debate. Judicial supremacy became the dominant way of thinking in the 20th century. Earl Warren was perhaps its apotheosis, but the idea pervaded both the Left and the Right. Judicial supremacy was definitely what you were taught in school. The Supreme Court endorsed it outright in an important precedent called Cooper v. Aaron (1958).

Whole Women’s Health v. Jackson, seems to me to come down to a simple issue: Congress has not granted the judicial branch the authority to resolve this dispute, because Texas engineered its law specifically to thwart Congress’s prior grants of appellate authority.

One half of the court, led by Gorsuch, adopts the departmentalist view: this law may be violating our court’s precedents, but Texas has successfully dodged our jurisdiction, except for one little technicality. And yes, Texas could fix that technicality in the future. And yes, this One Weird Trick could be used by other states, against other constitutional rights—but we are limited by what Congress has authorized us to do, so if some Justices or Texans want the Court to have the power to review this case, then they gotta go to Congress and ask Congress to grant it. (Gorsuch says this on p17 of his slip opinion.)

The other half, led by Roberts, adopts the supremacist view: Texas has successfully dodged our precedents, but we are guarantors of the Constitution. We have both the right and the duty to extend our own jurisdiction—as we have done before, in Ex Parte Young—far enough that we will be able to defend the rights of all American citizens, whether it’s abortion rights or gun rights or religious rights. Justice Sotomayor even concludes her opinion by giving me the perfect wrap-up to this blog post lionizing the judicial supremacist decision in Cooper v. Aaron:

In its finest moments, this Court has ensured that constitutional rights “can neither be nullified openly and directly by state legislators or state executive or judicial officers, nor nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes . . . whether attempted ‘ingeniously or ingenuously.’” Cooper v. Aaron (1958) Today’s fractured Court evinces no such courage. While the Court properly holds that this suit may proceed against the licensing officials, it errs gravely in foreclosing relief against state-court officials and the state attorney general. By so doing, the Court leaves all manner of constitutional rights more vulnerable than ever before, to the great detriment of our Constitution and our Republic.

If the idea of judicial supremacy loses steam at the Supreme Court, it will transform the relationship between our three branches of government in ways we can’t really begin to predict. Obviously it would spell the end for major judicial supremacist decisions like Roe/Casey. It could even doom Griswold or Pierce v. Society10, and that possibility had already heightened tensions. But today’s decision in Whole Women’s Health put the justices in direct confrontation over the meaning of Marbury v. Madison. Nobody saw that coming even a year ago. And very few people seem to recognize that it’s even happening now.11

That, I think, might explain the level of alarm and anger in the dissenting opinions… especially for John Roberts, who with each passing day seems to fancy himself less an umpire, more a philosopher-king, and who would not thrive as the mere head of a co-equal branch.12

Fun fact: same clinic as the one that sued in the Supreme Court’s odious 2016 Hellerstedt decision.

Very, very little, because it hinges on particulars of the Texas Health and Safety Code that I neither know nor understand.

A GOP-nominated SCOTUS justice retiring specifically to let a Democrat replace him would still be very surprising. All I mean is that the chances have gone up from 0.000% to 0.9% or 1%.

Depending on the particulars of the Texas Health and Safety code that I still neither know nor understand.

If so, it seems to have succeeded! This decision was not even the most-read story in the Politics section of today’s Minneapolis Star Tribune. I haven’t seen the physical St. Paul Pioneer Press yet, but I couldn’t find it on their website home page, so I’m guessing it’s not on A1.

“Given the ongoing chilling effect of the state law, the District Court should resolve this litigation and enter appropriate relief without delay.” (p2, Roberts concur/dissent)

“I trust the District Court will act expeditiously to enter much-needed relief.” (p2, Sotomayor concur/dissent)

I would like it on the record that I posted on Reddit that this case was about judicial supremacy before Josh Blackman posted about it on Reason (twice! he did another while I was writing this post!). I agree with him, it’s actually a little creepy how he came up with the same Lincoln parallels I did, but I didn’t steal this from him. (On the other hand, I totally did steal the stuff about the declaratory judgment from him.)

Other courts, like the circuit courts of appeals, have zero constitutionally-guaranteed jurisdiction. Their jurisdiction is whatever Congress says, and no more. (At least, on the departmentalist view.)

…and if it weren’t so late at night I’d probably even be able to come up with a judicial supremacist case that isn’t also a substantive due process case!

See footnote #5, regarding newspapers. And see if you can find a newspaper story that mentions Marshall, Marbury, supremacy, Congress, the All Writs Act, or Cooper. They’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg, the distracting abortion shiny.

I remind the reader again that I used to love John Roberts—even after the Right turned on him.